Every once and a while you run into an article on the internet that’s just too good to just make a bookmark (or some similar technique that allows you to store the URL to that previous piece of useful information). I have been on the internet long enough to know that no matter how good an article might be, just wait long enough and it will be gone, some day… So I decided to store these kinds of articles right here, on my own website, in what I call the Article Archive.

At my work, one of the things I do is install certificates on webservers, no big deal, but I tend to want to understand what I’m doing, what certificates are doing, how TLS is making the connection to my bank secure. And I don’t settle for “by using cryptography”. Patrick Nohe wrote this wonderfully complete breakdown of what a cipher suite actually is and what new things TLSv1.3 is bringing us. Let’s dive in!

Original: https://www.thesslstore.com/blog/cipher-suites-algorithms-security-settings/

Cipher Suites: Ciphers, Algorithms and Negotiating Security Settings

SSL/TLS Cipher suites determine the parameters of an HTTPS connection. And they’ve just undergone a facelift.

If you interact with SSL/TLS and HTTPS encryption long enough, you’re eventually going to come across the term “cipher suite.” And while that sounds like a fancy nickname for Alan Turing’s hotel room, cipher suites play a critical role in every HTTPS connection you make on the internet.

So, what are encryption ciphers? And what are cipher suites?

Ciphers are algorithms, more specifically they’re a set of steps for performing a cryptographic function – it can be encryption, decryption, hashing or digital signatures. Nowadays ciphers are dependent upon the advanced processing capabilities of computers. That hasn’t always been the case though. One of the first, well-known historical ciphers belonged to Caesar – the very first emperor of Rome and purveyor of fancy appetizer salads – who used it to communicate with his generals during military operations.

Over the years, ciphers have become more complex, but the logic behind them has stayed the same. Whether it was Caesar crossing the Rubicon, the infamous Enigma cipher of World War II or some of the algorithms of today—the idea has always been to encode or encipher a message in such a way that only the intended party can read it.

Today we’re going to discuss SSL/TLS Cipher Suites – groups of ciphers that help secure an HTTPS connection – then go over their various parts and finish by looking at what’s changed between TLS 1.2 and TLS 1.3.

Let’s hash it out.

Cipher Suites – Some Background

As we just covered, a cipher is really just an algorithm, or a set of steps that are used to perform a specific mathematical function – be that encryption, hashing or digital signatures. Ciphers have always had a basis in math, even Caesar’s primitive shift cipher required counting forward a designated number of spaces in the alphabet to encrypt something.

I’m going to use Caesar’s cipher to explain some basic concepts that will be useful later when we get into modern cipher suites. The piece of data or information – it’s all digital now, though historically there’s typically been some kind of ink and paper/parchment involved. Anyway, that original unencrypted piece of data would be referred to as the plaintext, as it’s easily readable in its raw form. After the encryption process has been performed, it becomes a piece of ciphertext and should ideally be unreadable to anyone without the private key.

Keys vs. Algorithms

Encryption is performed by keys, but it’s important to square how keys and algorithms/ciphers fit together.

The algorithm or cipher used is just that, it’s a sequence of steps that must be used to encrypt the plaintext.

Depending on the cryptosytem, either the values within that algorithm, or the value the algorithm arrives at itself, are the keys.

We’ll clarify that point in a minute, just think of it this way: the algorithms are the general principles/rules used by a given cryptosystem, the keys are what actually performs the function.

It’s just Math

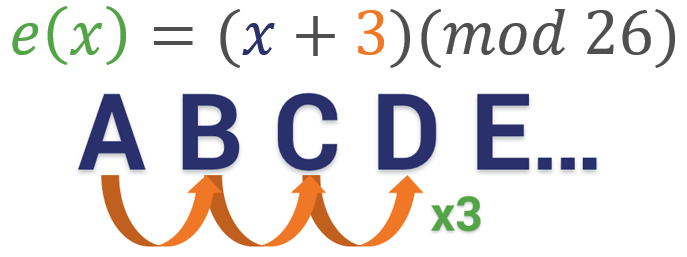

Sometimes it’s best to illustrate with an example so let’s go back to Caesar’s cipher and illustrate. In Caesar’s cipher, the actual algorithm is:

Ok, now let’s take a closer look at each component.

| Variable | Description |

| x | x represents the raw input, in this case x refers to whatever letter we’re shifting |

| e(x) | e(x) represents the encrypted value |

| k | k represents the key |

| mod | mod represents the modulus |

In Caesar’s cipher, the key is simply the number of spaces you decide to shift the letters. So, in the example below the key would be 3. We’re shifting everything three spaces forward.

Now let’s add in the modulus. Modular arithmetic wraps around after it reaches the modulus, which is basically the end of the line, the number cap – however you want to think about it. With the alphabet, the modulus is obviously 26. There are 26 letters, so if you want to move a “Y” three spaces forward you have to wrap around and start back at 1 (or A) again. So in this instance, the equation would be B = (Y + 3)(mod 26).

Modern Ciphers & Cipher Suites

It’s no different at the digital level. The math is far more complicated now – no human could do it efficiently – but the concept is still the same. It’s all just math. Now let’s apply what we learned about algorithms in general to SSL/TLS and HTTPS connections.

An HTTPS connection is actually a fairly complicated process. Last week we took a deep dive on the TLS handshake. This is the process where a client and server agree on a mutually support cipher suite and then use the chosen cipher suite to negotiate a secure connection.

Part of what makes the handshake so complicated is that it leverages several different cryptographic functions to achieve the HTTPS connection. During the handshake, the client and server will use:

- A key exchange algorithm

- A bulk encryption cipher

- A digital signature scheme

- A Hash/MAC function

These ciphers all work together at various points to perform authentication, key generation and exchange and a check-sum to ensure integrity.

In order to determine what specific algorithms to use, the client and server start by deciding on a cipher suite to use. Cipher suites are collections of these algorithms that can work together to perform the handshake and the encryption/decryption that follows. At the outset of the connection both parties share a list of supported cipher suites and then decide on the most secure, mutually supported suite.

The math is more complicated now… but the underlying concepts are still the same. It’s all just math.

There are 37 TLS 1.2 ciphers and five TLS 1.3 ciphers. Understanding their different parts is key to understanding HTTPS connections and SSL/TLS itself. Let’s start with an overview of TLS 1.2 – as it’s still the more common version of the protocol – and then we’ll talk about what’s improved in TLS 1.3.

What is a TLS 1.2 Cipher Suite?

As we covered in the last section, a Cipher Suite is a combination of algorithms used to negotiate security settings during the SSL/TLS handshake. When the ClientHello and ServerHello messages are exchanged the client sends a prioritized list of cipher suites it supports. The server then responds with the cipher suite it has selected from the list.

Cipher suites are named combinations of:

- Key Exchange Algorithms (RSA, DH, ECDH, DHE, ECDHE, PSK)

- Authentication/Digital Signature Algorithm (RSA, ECDSA, DSA)

- Bulk Encryption Algorithms (AES, CHACHA20, Camellia, ARIA)

- Message Authentication Code Algorithms (SHA-256, POLY1305)

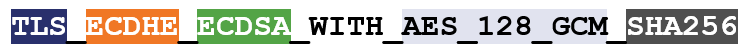

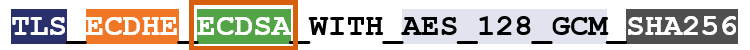

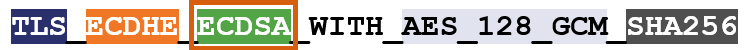

So, for instance, here’s an example of a cipher suite:

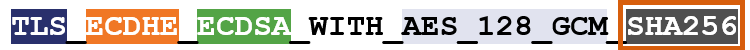

I’ve color-coated it to help you distinguish between the ciphers.

TLS is the protocol. Starting with ECDHE we can see that during the handshake the keys will be exchanged via ephemeral Elliptic Curve Diffie Hellman (ECDHE). RSA is the authentication algorithm. AES_128_GCM is the bulk encryption algorithm: AES running Galois Counter Mode with 128-bit key size. Finally, SHA-256 is the hashing algorithm.

By the end of this article all of that will make sense.

During the TLS 1.2 handshake it’s going to play out like this:

- Client and Server determine a mutually supported cipher suite

- Server sends its certificate and public key

- Client authenticates the certificate & digital signature

- Key exchange functions are performed to generate symmetric session keys

- Encryption begins; HMAC is used to ensure the handshake wasn’t tampered with

Obviously, that’s incredibly condensed, if you’re interested check out the full TLS Handshake article, but hopefully you can see where each cipher/algorithm comes into the picture.

Taking a Closer Look at the SSL/TLS Handshake

In Everything Encryption By Patrick Nohe

There’s a lot going on underneath the hood when you connect to a website via HTTPS. First and foremost, everyone needs to… shake hands?!

Unfortunately, TLS 1.2 has 37 different cipher suites to choose from and not all of them are still considered secure. You may be wondering how you wind up with nearly 40 different cipher suites. It’s two-fold. For one, TLS 1.2 has been around about 10 years, meaning there’s been plenty of times for new algorithms to arrive and old ones to phase out. And as that happens, the IANA, the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority, the organization that administers all of this, has to keep creating new combinations of ciphers – new cipher suites – owing to the fact that four different algorithms are required and there are myriad possible combinations.

Of course, not all of the algorithms play nice together, but enough do that there are 37 approved TLS 1.2 cipher suites in use today.

Let’s dive a little deeper into the four different components of the TLS 1.2 cipher suite. But first let’s talk a little bit about the two different kinds of encryption that you see in SSL/TLS.

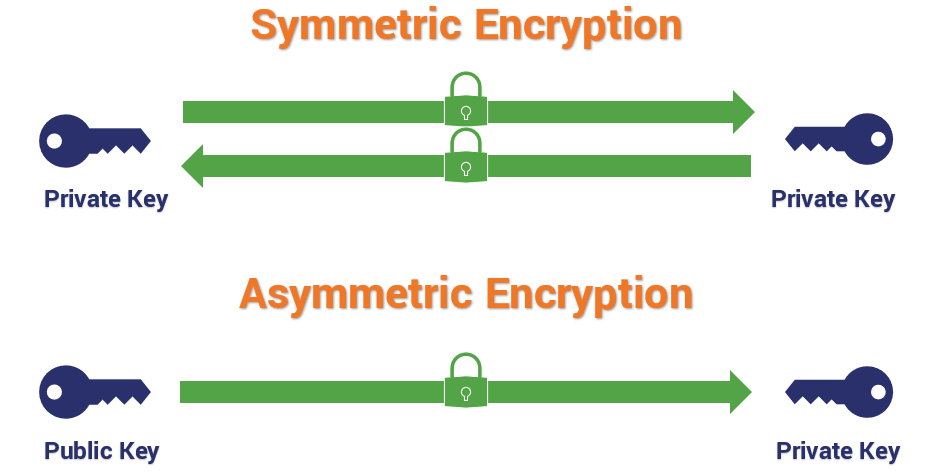

Two Kinds of Encryption

One of the biggest points of confusion when it comes to SSL/TLS centers around the types of encryption that are used. That has to do with how SSL certificates are advertised. And this really shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise given the fact the industry has never taken the time to correct everyone on the fact that we’re now using TLS certificates.

The 2048-bit key associated with your SSL certificate is used to help negotiate the HTTPS connection, but its role is actually a lot narrower than most people are led to believe. And 2048-bit keys are far from the only option when it comes to public key cryptosystems. ECDSA uses much smaller keys to accomplish a similar function.

We just seem to be fixated on the 2048-bit private key because it sounds more impressive. And we can trot out the, “it would take over a quadrillion years for a modern computer to crack this key and we’ll all already be dead by then!”

But, arguably, the bulk cipher and the symmetric key you end up using DURING the connection are equally, if not more important than the public/private key pair.

Symmetric encryption involves two keys that are the same, or as the name quite cleverly implies, are symmetric. Both keys can perform both functions: encryption and decryption. This is the type of encryption that you’re actually using to communicate with the site you’re visiting.

Conversely, with asymmetric encryption, you are talking about different keys with different abilities. When encryption is asymmetric, one key encrypts and the other key decrypts. Asymmetric encryption, which typically takes the form of RSA with TLS 1.2, is responsible for verifying digital signatures and, when RSA key exchange is in use, it’s for encrypting the pre-master secret that will be used to derive the symmetric session key. But RSA is not the only key exchange mechanism in use, so 2048-bit keys are actually kind of an odd thing to advertise.

Symmetric encryption keys, which are typically AES or Advanced Encryption Standard, range from 128-bit to 256-bit in key size. And this is completely efficient and secure for symmetric encryption, where computational hardness needs to go hand-in-hand with usability/performance.

How strong is 256-bit Encryption?

In Everything Encryption By Patrick Nohe

256-bit encryption strength gets tossed around all the time, but most people have no idea what 256 bits of security means or how strong it actually is. Let’s hash it out.

Those 2048-bit asymmetric RSA keys are expensive to compute with, and add latency to handshakes. They’re also vulnerable to padding attacks in some implementations.

Long story short, both asymmetric encryption and symmetric encryption are represented here, but the symmetric encryption is more relevant in the context of cipher suites.

Now let’s look at the four different components of a cipher suite.

Key Exchange

The first spot in the TLS 1.2 cipher suite is designated for the key exchange mechanism that will be used.

Key exchange refers to the actual process that’s used to transmit those symmetric session keys (or the key shares they’re derived from), but it’s not the only algorithm used in the generation process. That’s confusing, I know. The key exchange portion of the handshake determines the parameters for the key generation, but the hashing algorithm also plays a role in generating keys by providing Pseudo-Random Functions (PRFs), typically as a cryptographically secure pseudo-random number generator (CSPRNG).

The important thing to take away is that the key exchange mechanism that’s chosen isn’t solely responsible for generating the actual key.

RSA

RSA is named after the gentlemen that created it: Rivest, Shamir and Adleman. This is the most common asymmetric cryptosystem. It uses exponentiation of prime numbers and has a wide range of applications. With SSL/TLS you commonly see RSA used in the context of key exchange. Again, this is where all those 2048-bit (and 3072- and 4096-bit) keys come from.

Every handshake, regardless of whether or not RSA is chosen, begins with a Client and Server Hello where they exchanged randoms, a client random and a server random.

The way RSA operates is fairly simple, once the client and server decide to use a cipher suite that includes RSA key exchange – and after the client has authenticated the server:

- The client uses the public key that the server sent over to encrypt a pre-master secret and transmit it.

- The server uses its private key to decrypt the pre-master secret.

- Both parties use PRFs, the client random, the server random and the pre-master secret to derive the master secret.

- Both parties use the master secret and more pseudo-random functions to calculate the session key.

It’s during those last two steps, 3 & 4, when mixing the master secret and deriving the session key, where the hashing algorithm’s pseudo-random functions are leveraged.

RSA key exchange has been useful for a long time, but it’s at the end of its life. TLS 1.3 has done away with RSA key exchange – in addition to all other static key exchange mechanisms – because of known vulnerabilities.

Diffie-Hellman & Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman

Named after Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman, this is a key exchange protocol, it’s NOT an asymmetric encryption protocol in the same vein as RSA though. The problem that Diffie and Hellman (using work inspired by Ralph Merkle) set out to solve was how to exchange a secure key over an unsecure network with an attacker watching.

What they came up with was Diffie-Hellman key exchange, which was eventually succeeded by RSA, but has now re-taken the advantage.

Diffie-Hellman key exchange works like this:

- After exchanging randoms (g & p), both the client and server select their own pre-master secret (a & b, respectively) and compute a similar equation – ga mod p = A, & gb mod p = B.

- The value each arrived at (A & B) is sent to the other, and both parties repeat the same operation – Ba mod p, & Ab mod p.

Each party provides what is called a “key share,” and they each arrive independently at the shared session key. There is a rule of modular exponentiation that dictates this.

If that was a lot of math, the key takeaway is that: with Diffie-Hellman no asymmetric encryption actually takes place during the key exchange, rather the two parties mutually arrive at values that can be used to derive the session key.

Now let’s talk about Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman, which is basically just a modern-day iteration of Diffie-Hellman undergirded by elliptic curve cryptography as opposed to some other cryptosystem. Basically, it uses points plotted on an elliptic curve as the basis for its calculations.

There are a couple of things to keep in mind with Diffie-Hellman, first of all – it lacks a true authentication mechanism when being used ephemerally. Ephemeral keys are temporary and usually not authenticated.

Second, as we just mentioned, in TLS 1.3 all static key generation/exchange mechanisms were deprecated. That’s what basically killed RSA, and it also does away with DH schemes that aren’t ephemeral, too. ECDHE or Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman Ephemeral is now the standard for key exchange.

That’s because Perfect Forward Secrecy is mandatory in TLS 1.3. Perfect Forward Secrecy protects individual sessions from being decrypted, even in the event a certificate’s private key is compromised. Static key exchange schemes couldn’t support that. Ergo, they’re gone.

PSK

Typically written as TLS-PSK, this is a cipher that provides secure communication based on pre-shared symmetric keys exchanged between parties in advance. We’re not going to spend a lot of time on PSK as it’s fairly rare outside of highly regulated network environments and we definitely wouldn’t advice its commercial use. It was not included in TLS 1.3.

Digital Signature/Authentication

Here’s where things start to get confusing – and you can also begin to see how these cipher suites have multiple permutations. For example, there are four common iterations of Diffie-Hellman:

- Diffie-Hellman (DH) *deprecated in TLS 1.3

- Diffie-Hellman Ephemeral (DHE)

- Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH) *deprecated in TLS 1.3

- Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman Ephemeral (ECDHE)

But none of those can handle authentication, so they have to be paired with an authentication scheme – historically, that’s been either DSA, RSA or ECDSA.

RSA can function as BOTH a key exchange mechanism, as well as provide authentication with digital signatures. You can even use Diffie-Hellman and RSA together. All these combinations and we’re not even halfway through the cipher suite.

The Signature algorithm is the second algorithm in the TLS 1.2 cipher suite.

One more thing, you sometimes people refer to the type of SSL certificate on the basis of its signing algorithm. For instance, when someone says they have an RSA SSL certificate or an Elliptic Curve SSL certificate, they’re alluding to the signing algorithm. That’s because this is determined during the generation of the CSR. Keep that in mind, because it’s part of why TLS 1.3 cipher suites don’t include the signing scheme.

RSA Digital Signatures

Digital Signatures are one of the best ways to authenticate another party. Using the digital signature, the client can verify the authenticity of the SSL/TLS certificate, and in the case of cipher suites using Diffie-Hellman, verify ownership of the public/private key pair.

With RSA, the client (and sometimes the server if a client SSL certificate is in use) checks the authenticity of the certificate being presented by running a series of checks. It looks at the certificate chain by following the digital signatures left by the signing CA back to one of the roots in its trust store. It checks the validity dates and the revocation status of the certificate, too. Then it uses the associated public key to verify the private key’s signature.

The final verification that the server is in possession of the private key comes during the key exchange, when the client encrypts the pre-master secret with the public key and the server decrypts it with private key.

Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm

As we mentioned earlier, Diffie-Hellman key exchange has no authentication mechanism in ephemeral mode. That means it needs to be paired with an authentication mechanism. As we just covered, RSA is an option, the other popular method is called the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm, which has now replaced DSA. The way ECDSA works is very similar to RSA at the outset, but with one major difference.

Whereas both methods check the certificate the same way, when Diffie Hellman is in use the actual key exchange portion can’t be used to prove possession of the private key. Instead, the server takes the two randoms (client and server) as well as the Diffie-Hellman parameters it has chosen (its pre-master secret) and encrypts them all with its private key. This serves as its de facto digital signature. The client will use the public key to verify the signature and thus, ownership of the private key.

What about DSA?

The Digital Signature Algorithm, which was already on its way out, has been entirely removed from TLS 1.3. While there is some debate over how secure DSA still is, what really hamstrung it was key size. DSA uses keys that are comparable in size to RSA: 1024-, 2048-, 3096-bit keys, that – as we covered – are expensive to compute with. By comparison, it’s Elliptic Curve-based counterpart, ECDSA, uses keys that are typically 224- or 256-bit.

Edwards-curve Digital Signature Algorithm

EdDSA is a digital signature scheme that removes the need for pseudo-random number generation from the equation. We touched on PRFs earlier, they’re typically generated using the designated hash function, but they’re not always actually random. In fact, the secret values that are produced, which are sometimes called nonces, can leak private keys if the RNG is ever broken/made predictable.

Instead, EdDSA picks a nonce based on a hash of the private key and the message, which means after the private key is generated there’s no more need for random number generators. EdDSA is one of the three digital signature schemes approved for use in TLS 1.3.

Bulk Encryption Ciphers

While neither of the previous two categories are included in TLS 1.3 cipher suites, these next two – bulk ciphers and hashing algorithms – are included.

Your bulk cipher is what will be used for the actual symmetric encryption that will occur during an HTTPS connection. Traditionally there are two kinds of bulk cipher:

- Block ciphers

- Stream ciphers

A block cipher, as its name might suggest, encrypts data in blocks of a pre-determined size. Unlike with asymmetric encryption though, this isn’t necessarily linked to key size. A 256-bit key doesn’t always create 256-bit blocks of ciphertext. For instance, AES produces 128-bit blocks, regardless of key size.

At any rate, after data is encrypted into blocks, it’s then incumbent upon the recipient to decrypt the blocks and piece them back together so that the information is intelligible.

So, what happens if the data being encrypted isn’t exactly the right size? That’s extremely common. It means the data needs to be segmented into appropriately sized chunks, and any unfilled space needs to be padded with throwaway data to make it fit, which can open attack vectors and is just, generally, inefficient.

The other type of cipher is a stream cipher, which encrypts data in long pseudorandom streams. When you see the cipher written out, the bulk cipher is the third algorithm listed and it typically includes a modifier that dictates how the bulk cipher should be run.

For instance, in the example above we’re running AES or Advanced Encryption Standard, running in GCM or Galois Counter Mode, using 256-bit keys. AES is, by design, a block cipher. But it can be run as a stream cipher in counter mode.

We’ll get to it in a second, but in TLS 1.3, the bulk cipher is now expected to be an AEAD or Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data algorithm, meaning that it can not only encrypt the communication but also authenticate it. Originally these two functions had been performed separately, but issues with errors, and just difficulty implementing it correctly in general, motivated the IETF to combine the two functions in TLS 1.3.

We’ll get into the authentication portion of the AEAD when we discuss hashing algorithms in the next section.

AES

Advanced Encryption Standard, a.k.a. Rijndael, is a NIST-approved encryption cipher with a block size of 128 bits, and symmetric keys with lengths of either 128, 192 or 256 bits. It’s actually the first and only publicly available cipher that’s approved by the NSA to encrypt “Top Secret” data. AES was the successor to the Data Encryption Standard, which was first published in 1977.

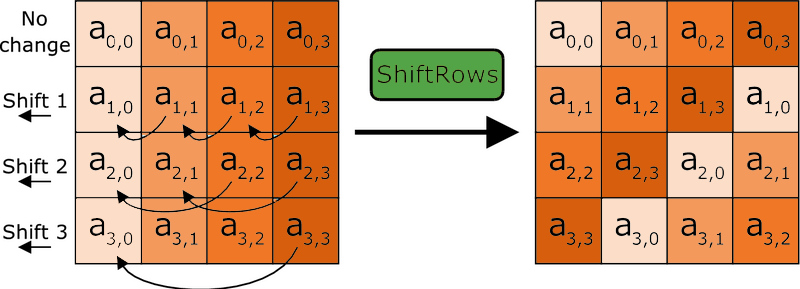

AES works in an interesting way. It operates on 4 x 4 arrays of bites called a “state.” As we just said, AES is naturally a block cipher and its blocks are 128 bits. It’s key sizes actually refer to the number of “rounds” that the plaintext will be put through as it’s encrypted.

- 128-bit key = 10 Rounds

- 192-bit key = 12 Rounds

- 256-bit key = 14 Rounds

Each round the plaintext undergoes includes substitutions from a lookup table, rows shifted cyclically and a linear mixing operation that combines the four bytes in each column. For decryption a set of reverse rounds is used.

AES is the most commonly supported bulk cipher in TLS 1.2 & TLS 1.3 cipher suites. When run in Galois Counter Mode and CCM (Counter with CBC_MAC) mode, AES functions as a stream cipher with message authentication capabilities (an AEAD).

CBC just means that AES is being run in block cipher mode. I realize that may be confusing because we just discussed how block ciphers aren’t supported by TLS 1.3. With CCM, the counter mode means you’re running the cipher in stream mode, the CBC_MAC portion is for the message authentication part of the AEAD.

CHACHA20_POLY1305

CHACHA20_POLY1305 is a relatively new option for SSL/TLS, having been finalized in 2015. It’s a stream cipher that works alongside POLY1305, which works as an authenticator to accomplish AEAD. CHACHA is much faster than AES in software-only implementations. It’s about 3 times faster on platforms that don’t have specialized AES hardware. Both CHACHA and POLY1305 are considered easy to implement and provide excellent performance.

CHACHA20_POLY1305 uses a 256-bit key and a 96-bit nonce. During the encryption/authentication process, a one-time POLY1305 key is generated from the 256-bit key and the nonce. CHACHA20 then performs its encryption, using the same key and nonce. Finally, POLY1305 authenticates the message. The output is a piece of ciphertext the same length as the plaintext that was input, as well as a 128-bit MAC tag.

POLY1305 can also be used as a hashing algorithm on its own.

Other Bulk Ciphers

Here are some ill-advised SSL ciphers from handshakes past.

DES/Triple DES

The Data Encryption Standard, originally nicknamed Lucifer, was the first publicly available civilian block cipher. The version of DES we know today is a revised version of the original. DES is more notable for what it inspired than what it actually does. It’s encryption, by today’s standards, is fairly pedestrian with block sizes of 64 bits and a key size of 56 bits. Those key sizes were already considered worrisome as early as the 1970s, but by 1998 the EFF had demonstrated a special-purpose machine designed just to break DES and that was pretty much the final nail in its coffin.

Triple DES is an extension of DES that triple-encrypts each block with either two or three different keys. This still is sufficient for many regulatory bodies though. NIST, for instance, only allows Triple DES in its three-key version. And even at that, 3DES only provides 112 bits of security.

RC4

Ron’s Code 4 or Rivest Cipher 4 – it’s known by both names – invented by RSA’s Ron Rivest, is impressive for its speed and simplicity. It is no longer, however, impressive for its security, which has been shown to be wanting across multiple vulnerabilities. Originally a trade secret, it was leaked in September 1994 to a mailing list and then cracked within days.

Though it was originally recommended as a workaround for the BEAST attacks back in 2011, by 2013 new attacks demonstrated that it would be feasible to break RC4-encrypted TLS. Improvements to the attacks in 2015 made it even more viable and within months RC4 had been deprecated. RC4 has two successors in RC5 & RC6, neither is acceptable for TLS 1.3.

Camellia

A symmetric key block cipher with similar capabilities and key sizes to AES. It was developed in Japan by NTT and Mitsubishi and is approved by the ISO/IEC, EU and the Japanese CRYPTREC project. As of now, in its full implementation Camellia has not been broke. While there were Camellia TLS 1.2 cipher suites, it’s not included in TLS 1.3.

ARIA

Another block cipher that is similar to AES, ARIA was developed by a group of researchers in South Korea in 2003. Like AES, its key sizes refer to the number of rounds that occur during encryption. Like Camellia, it is also not included in TLS 1.3.

Data Integrity/Authentication

Not to be confused with server/client authentication, the hashing algorithm that has traditionally been associated with SSL/TLS has historically handled message authentication and pseudo-random functions. As we’ll discuss in just a moment, that’s been rethought for TLS 1.3, with HKMF or HMAC-based key derivation function.

Let’s start with TLS 1.2 and the Hash-Based Message Authentication Code which has traditionally appeared as the fourth algorithm in the cipher suite.

Hash-Based Message Authentication Code (HMAC)

This is a type of message authentication that uses cryptographic hashes to both authenticate a message and ensure data integrity. Historically this has been done by two main cipher families: MD5 and SHA.

MD5 is totally outmoded now. It was once a highly used hash function that produced 128-bit digests or hash values. When you hash something, you’re mapping data of any length to a fixed-length output. In order for a hashing algorithm to be considered secure, it has to be resistant to collisions. A collision occurs when two disparate inputs create the same value. This renders the algorithm useless. MD5 was found to be embarrassingly insecure around 2012. Collisions can be found trivially on a home computer within seconds.

SHA replaced MD5 and has served adequately ever since. In 2016 the entire SSL/TLS industry shifted away from SHA-1 as the standard hashing algorithm and upgraded to SHA-2. Google managed to create a SHA-1 collision later that year. SHA-2 is still considered a secure hashing algorithm and is included in TLS 1.3. It just plays a different role.

AEAD vs HMAC

With a traditional HMAC, the message is hashed along with a secret key or Message Authentication Code, we’ll get into HMAC in-depth in the future, the important takeaway is that the hash function basically serves as a check-sum, arriving alongside the ciphertext and indicating whether the message was tampered with. The recipient will use the same key to run the same hash function and compare values.

Historically there has been three different approaches to this:

- Encrypt-then-MAC

- MAC-then-Encrypt

- MAC-and-Encrypt

SSL/TLS, perhaps foolishly, has always used a Mac-then-Encrypt approach for message authentication. Or, more accurately, a MAC-then-Pad-then-Encrypt model. This has been problematic because it opens itself up to padding oracle attacks. It’s also somewhat inefficient, because the client or server have to use resources to decrypt the message first, which is wasteful if it can’t be authenticated. Attackers can actually send a bunch of unauthenticated requests to a server and overwork it by making it decrypt a bunch of garbage.

TLS 1.3 goes in a different direction with AEAD. It MACs and Encrypts simultaneously, shutting the window on padding attacks and saving clients and servers time and resources by making it easier for them to discard unauthenticated messages without having to decrypt them.

HMAC-based Key Derivation Functions

Sticking with TLS 1.3, hashing has seen a bit of an overhaul. We just talked about AEAD bulk ciphers, the message authentication that had originally be handled by the HMAC algorithm, has been offloaded to the bulk cipher now.

Instead, focus on the last three words in HKDF: Key Derivation Function.

Let’s go back to the key exchange conversation we had earlier and the pseudo-random functions that were used to mix keys during RSA key exchange and calculate them during Diffie-Hellman. HKDF provides a much more secure, much more random method for deriving those keys.

There are two primary stages: extract and expand.

The extract portion takes key input information (key shares, randoms, pre-master secrets) and optionally a salt, and then extracts a sufficiently secure pseudorandom key.

The expand stage is a mechanism where the algorithm expands the key to requisite size without compromising its computational hardness. RFC 5869, which specifies HKDF makes it extremely clear that the two stages should not be conflated. As we’ve discussed many times, the Random Number Generators that get used for pseudo-random functions are much more fallible than many would care to admit. Especially if the same seeds are re-used by many different implementations. Hence TLS 1.3’s focus on increasing the security of its pseudo-random functions to avoid some of the vulnerabilities that have surfaced lately.

Obviously, this is an incomplete list, there are dozens of other ciphers. But this should at least give you some more context when you see the lists of cipher suites we have in the next section.

TLS 1.2 Cipher Suite List

Here’s a list of the current RECOMMENDED cipher suites for use with TLS 1.2. We’re not going to publish all 37 of the ciphers that are available. These are the ones that are advisable:

- TLS_ECDHE_ECDSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256

- TLS_ECDHE_ECDSA_WITH_AES_256_GCM_SHA384

- TLS_ECDHE_ECDSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA256

- TLS_ECDHE_ECDSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA384

- TLS_ECDHE_ECDSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA256

- TLS_ECDHE_ECDSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA384

- TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256

- TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_GCM_SHA384

- TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA256

- TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA384

- TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA256

- TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA384

- TLS_DHE_RSA_WITH_AES_128_GCM_SHA256

- TLS_DHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_GCM_SHA384

- TLS_DHE_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA

- TLS_DHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA

- TLS_DHE_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA256

- TLS_DHE_RSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA256

- TLS_ECDHE_ECDSA_WITH_CHACHA20_POLY1305_SHA256

- TLS_ECDHE_ECDSA_WITH_CHACHA20_POLY1305

- TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_CHACHA20_POLY1305_SHA256

- TLS_ECDHE_RSA_WITH_CHACHA20_POLY1305

Again, you should be using Ephemeral Diffie-Hellman. Not only is it mandatory in TLS 1.3, it also facilitates Perfect Forward Secrecy, which guards against the decryption of individual sessions in the even the server’s private key is ever compromised.

What’s Different in TLS 1.3?

We’ve tried to point out when things have changed during each section, but we’ll go ahead an give a more comprehensive list here. Let’s start with the makeup of the cipher suite itself, then we’ll go back over the ways that the algorithms themselves have been updated for TLS 1.3 cipher suites.

Shorter Cipher Suites

The biggest thing you’ll notice about TLS 1.3 cipher suites is that they’re much shorter than their TLS 1.2 counterparts. That’s owing to two major things:

- The type of certificate is no longer listed (whether its RSA or ECDSA)

- They key exchange mechanism is not listed (always DHE or ECDHE)

That means that the number of negotiations that need to be done when determining encryption parameters has been reduced from four to two.

As you can see, TLS 1.3 cipher suites only include an AEAD bulk cipher and an HKDF.

The client goes into the handshake with the knowledge that Diffie-Hellman Ephemeral scheme will be used for the key exchange process. This means it can send its portion of the key share during the Client Hello.

That, in turn, can cut the TLS 1.3 handshake down to a single roundtrip, where the server responds with all the requisite information for the two parties to derive the session key and begin communicating securely during its Server Hello message.

Deprecation of Old Ciphers/Functionality

But the changes go well beyond just the length of the cipher suites and the reduced number of negotiations during the handshake. Things have also been made much more secure.

TLS 1.3 has eliminated:

- SSL Compression

- Static key exchange functions

- Block ciphers (CBC)

- Non-AEAD ciphers (MAC-then-Encrypt)

- Renegotiation of encryption parameters

It’s also dropped support for older, vulnerable SSL ciphers like:

- RC4

- DSA

- MD5

- SHA1

- Weak Elliptic Curves

- RSA Key Exchange

- Static Diffie-Hellman (DH, ECDH)

Because the structure of 1.3 cipher suites is different from its predecessors’, TLS 1.3 cipher suites will not be interchangeable with older TLS versions. That essentially means you’re going to need to have two different implementations if you plan on continuing to support TLS 1.2. And there’s nothing wrong with continuing to support TLS 1.2, either.

Until more companies in the hosting community make it a point to transition to TLS 1.3, shutting off TLS 1.2 would be foolish.

You should have already disabled TLS 1.1, TLS 1.0, SSL 3.0 and SSL 2.0 though. The PCI DSS deadline for deprecating SSL 3.0 was last Summer. The deadline for TLS 1.0 and TLS 1.1 is January 2020.

TLS 1.3 Cipher Suite List

Here are the five TLS 1.3 cipher suites that are supported by OpenSSL right now.

- TLS_AES_256_GCM_SHA384

- TLS_CHACHA20_POLY1305_SHA256

- TLS_AES_128_GCM_SHA256

- TLS_AES_128_CCM_8_SHA256

- TLS_AES_128_CCM_SHA256

There may be more cipher suites incoming as TLS 1.3 continues to gain its footing, but reducing the number of possible options was also one of the biggest considerations when the IETF was finalizing TLS 1.3, so if there are additional cipher suites added don’t expect the explosion of combinations we saw with the TLS 1.2.

What We Hashed Out (For the Skimmers)

For those that like to skim, here are the key takeaways from today’s conversation:

- Ciphers are algorithms, sets of instructions for performing cryptographic functions like encrypting, decrypting, hashing and signing. They can be symmetric or asymmetric, depending on the type of encryption they support.

- A Cipher Suite is a combination of ciphers used to negotiate security settings during the SSL/TLS handshake. During the handshake, the client and server exchange a prioritized list of Cipher Suites and decide on the suite that is best supported by both.

- TLS 1.3 the structure of Cipher Suites has changed, shrinking from four ciphers to just two and cutting then number of negotiations in half.